There is a common saying in the public transport policy debate that, "Supplying more highways simply creates more demand for their use."

No. This is wrong. This is lazy thinking resulted from simplistic comparison between increase in highway and increase in cars.

The real factors that create demand for private cars in a city with good public transport system are two: increasing population and increasing capital flow.

When (A) people who can afford private cars move into the city, and (B) people in the city becoming more able to afford private car, there is increase in private car usage and increase traffic jam, despite the availability of good public transport.

Unless the city restricts population growth and capital flow, there will always be increase demand for highway even when there is good public transport in place.

Take Hong Kong as example. The city has one of the best public transport system in the world. About 90% of the city's population use public transport. Yet, new highway and roads are still being built to cater the increase demand for road usage.

> Central - Wan Chai Bypass and Island Eastern Corridor Link: HK$36bil/RM19.21bil

> Central Kowloon Route: HK$42.36bil/RM22.61bil

> Road expansion for West Kowloon Reclamation Development: HK$845.8mil/RM451.45mil

> Hiram’s Highway Improvement: HK$1.77bil/RM944.75mil

> Widening of Tolo Highway/Fanling Highway: HK$4.32bil/RM2.3bil

(Ref: https://www.hyd.gov.hk/en/road_and_railway/road_projects/projects_under_construction.html)

These on-going highway and road construction projects cost about RM45.5bil. The amount spent on road projects alone in this city that has excellent public transport system is about the estimated cost of the Penang Transport Master Plan (PTMP).

Unless Hong Kong restricts population growth and capital flow, they will need to continue to improve their traffic dispersal network and public transport to cater to the increasing demand for public mobility.

The only possible experiment to disprove this observation is also one that no city with good public transport system is willing to conduct. It requires the city to restrict population growth and capital flow.

But this is not the point. The point is that it is wrong to conclude that supplying more highway will create more demand for private car usage, as if the availability of highway itself causes the increase in private car usage.

To pit the construction of new highway to disperse traffic against building good public transport infrastructure is a pseudo-conflict. No growing city adopts this pseudo-conflict as their principle to increase public mobility.

The NGOs' objection against PTMP is that it has plans to build highways and road to improve traffic dispersal network. They say that Penang has no good public transport system, so the focus should be to build one. But Hong Kong is spending billions to improve traffic dispersal network despite the fact that they have excellent public transport system and 90% of public transport usage. This is not only confined to Hong Kong. Other cities like Singapore and Zurich are doing the same.

This simple fact cannot register among the anti-PTMP NGOs because they have completely sold out to the pseudo-conflict mentioned above.

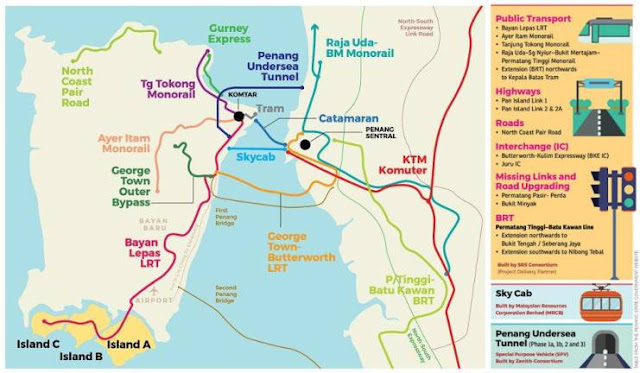

If Penang wants to continue growing, she has to continue to improve her traffic dispersal network and simultaneously build a good public transport infrastructure. This is precisely what the PTMP aims to do.

The same goes to any other city. To improve public mobility, we need to ditch the pseudo-conflict and get on with actual work by improving traffic network and public transport.

If Penang wants to continue growing, she has to continue to improve her traffic dispersal network and simultaneously build a good public transport infrastructure. This is precisely what the PTMP aims to do.

The same goes to any other city. To improve public mobility, we need to ditch the pseudo-conflict and get on with actual work by improving traffic network and public transport.